If you didn’t know by now, you should: last Monday, George Floyd died when a white police officer knelt on his neck for nine minutes. The fact that he is black, in a country where black people are unfairly scrutinized and made to endure higher rates of police brutality, has turned a single miscarriage of justice into an indictment of an unjust society; to comment on Floyd’s death is to also invoke the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Travyon Martin, and Michael Brown.

The protests surrounding Floyd’s death have garnered national attention for their scope and persistence. In many cities they proceed by a now-familiar beat: protesters, with signs held and voices raised, disrupt business as usual. In response, police are deployed, or in severe cases the National Guard. Standoffs between protesters and law enforcement ensue, arrests are made, tear gas is released.

On balance it seems like the protesters have nothing immediate to gain from this exercise. And that is indeed what some critics would want to say about these protests: that they accomplish nothing material. Yet the real power of protest lies in its ability to grab the nation’s attention. Protest is loud not because it is uncivilized but because it starkly points out that which is truly uncivilized: the devaluation of black lives. Through protest, the public is forced to acknowledge the issue being addressed and hopefully become sympathetic to the cause.

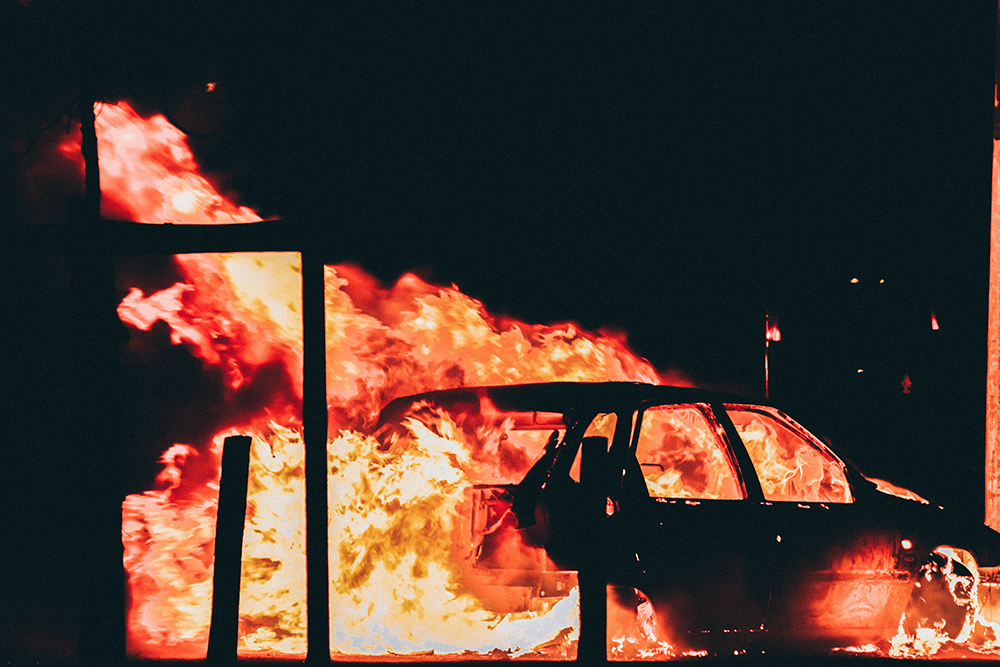

But the positive attention gained from protest has the potential to devolve into something less sympathetic when protests turn into riots and riots turn into looting. A riot is, no doubt, a response to valid emotions of anger and frustration, the same emotions that often drive protest. However, at the heart of many riots exists a sense of revelry in destruction and an engagement in destruction for its own sake. No, destroying and looting a Target will not cause many tears to be shed. On the other hand, looting and subsequently burning down local businesses does not accomplish the same goal as protest does. The general public may understand and support the sentiment behind protesting, but arson and looting are hard to get behind, to put it lightly.

For the sake of the cause, a clear distinction must be made between protesting and rioting. I’ve heard some of my peers make the argument that peaceful protests are ineffective. If they expect protest to result in immediate change every single time, then by that standard they are right. But real change, whether in policy or otherwise, stems from the will of engaged citizens. And engaging enough people to effect change requires a sustained effort, which every successful protest movement is. In contrast, riots ultimately serve to materially diminish communities and sour public opinion. Rather than engaging others in the issue at hand, they instead cause would-be allies to disengage.

I’m aware that some instances of rioting may be incited by bad actors looking to turn the public against the protesters. Such occurrences should of course be accurately identified and condemned. However, rather than demonstrating the futility of peaceful protest, this incitement to violence proves that protest is powerful enough to be considered a threat to its opponents. The response to incitement should not be to excuse all violence but to hold fast to peaceful protest.

We tend to pay attention to certain narratives that are contingent on the media we consume, the tribes we belong to, and our own personal biases. But the truth is not always where we first look for it; those of us that focus only on the riots and looting will not be able to fully accept the original injustice of George Floyd’s death. My hope is that in the end, this nation’s attention will be paid where it is due, and that real change may result. No matter how long it takes.